- >

- Exhibitions

- >

- Online and travelling exhibitions

- >

- Law and Order

Common for all gold rushes is that prospecting and social phenomena relating to it have been controlled by legislation either before or during the rush.

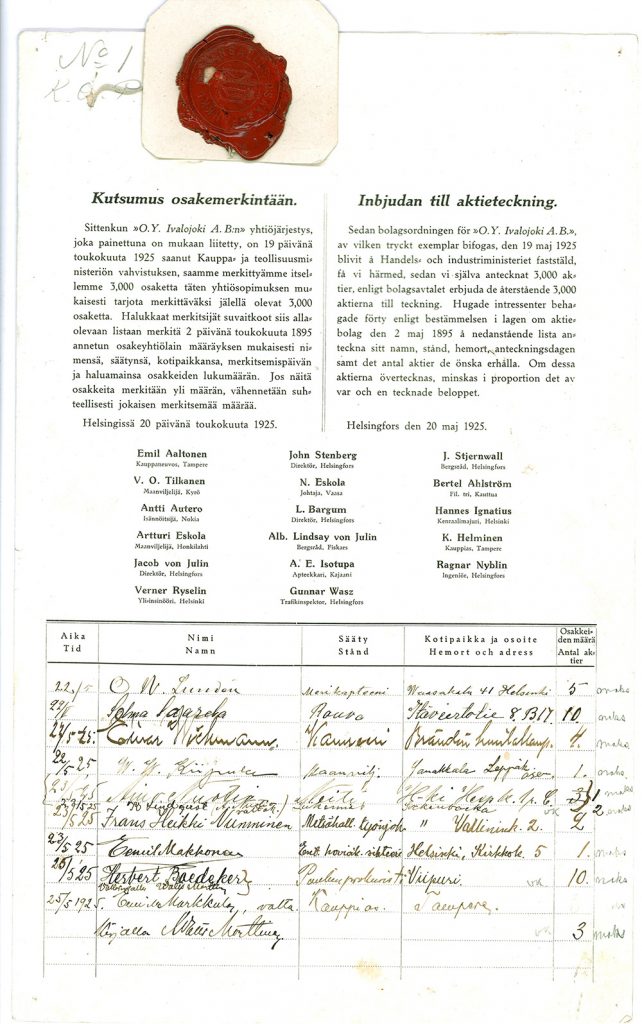

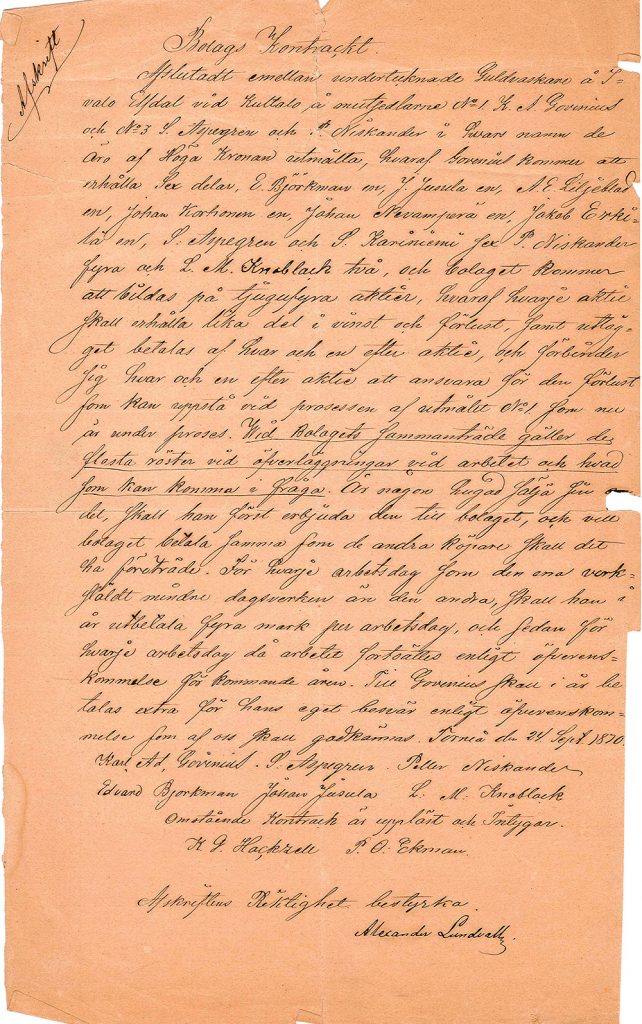

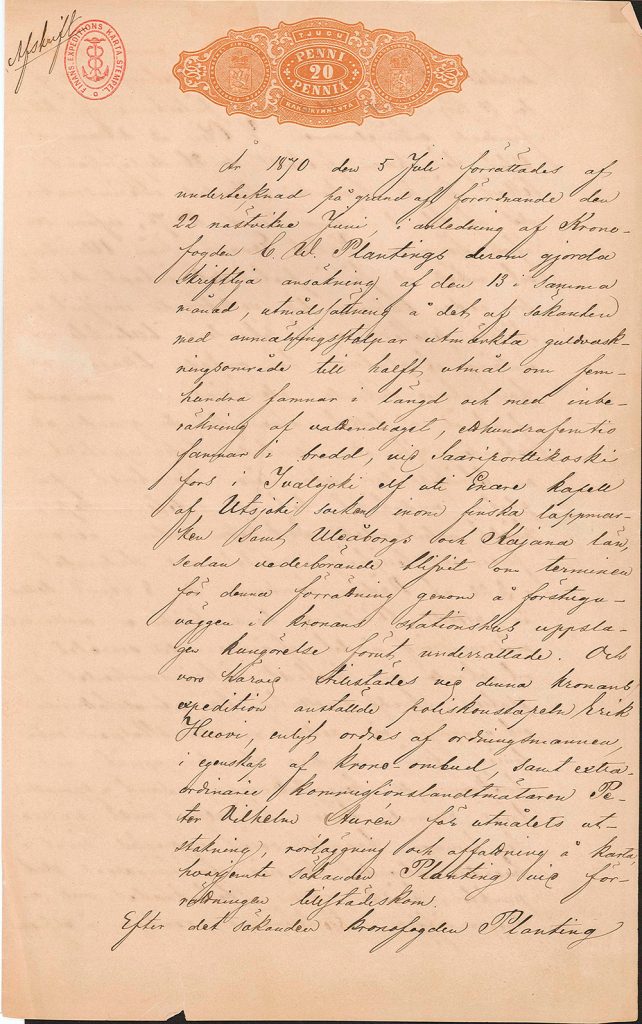

Law during the Ivalojoki gold rush

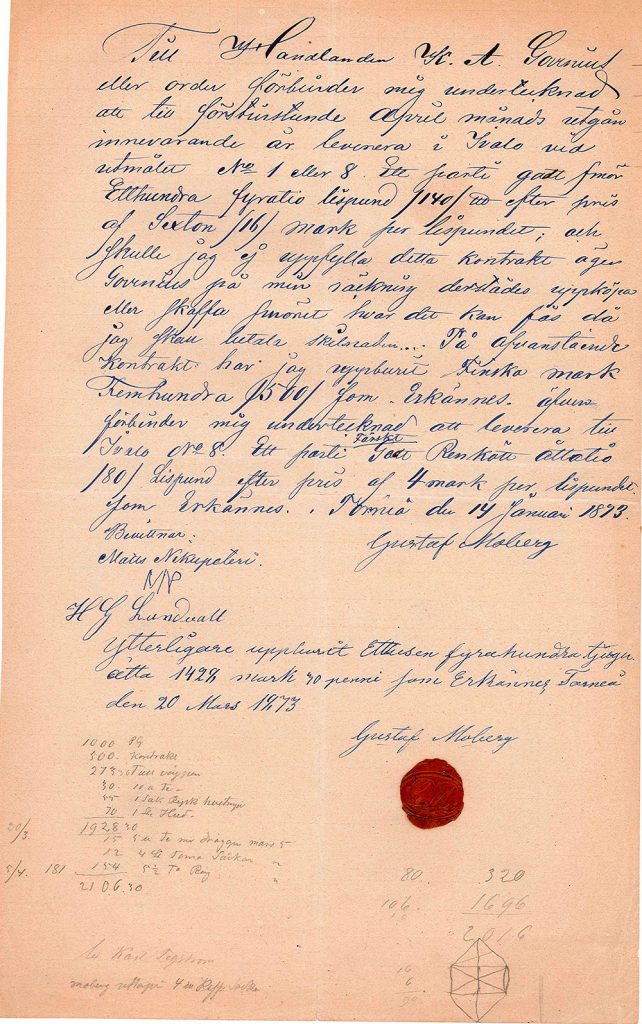

Gold fever in Finnish Lapland did not provide the same scale disorders or the number of jobbers as the big gold rushes around the world, California and Ballarat as examples. However, even for northern Lapland, it was necessary to create common rules to ensure order, thus the emperor of Russia, Alexander II, set an act concerning gold prospecting in Lapland of Finnish Grand Duchy. Furthermore, an officer house Kultala Crown Station was built for summer 1870. It served as a base for about 40 officers, who saw that the rules were followed, took in reports, admitted prospecting permissions etc.

The gold prospecting regulation/act itself took small steps in a democratic direction, partly because the leaders of Grand Duchy of Finland were quite determined. Rather many nobles and big company owners in Russia wanted the regulation to concern only them, but at the end, gold prospecting was allowed to every man with a good reputation. In retrospect, the law itself was a peculiar combination of Eastern and Western legislation, but it served the purposes of those days.

How did the prospectors obey the law? In northern Lapland quite well, though officers had to resolve cases related, for example, to the borders of the claims. There was a saloon near Kultala Crown Station, so it was difficult to avoid occasional fights when tired men – or part of them – took that one drink too much. In general, things went smoothly, though there were 500-600 prospectors in the area during the busiest first years. Also, obeying the law was strictly overseen. Information about happenings and some disorders during the bigger gold rushes elsewhere in the world made the act quite strict. Especially section number 52 of the law defined specifically what a prospector can do and what he cannot do. Prospectors were made also to keep an eye on each other.

Another thing, however, is how the duty related to reporting and tax paying was followed – despite the strict act. Stories tell that during the early years of gold rush part of the prospectors smuggled their gold across the border to Norway. This happened for two reasons: firstly, they didn’t need to report that gold, which meant they didn’t have to pay taxes to the emperor for that gold. Secondly, the price of gold was higher in Norway than in the Grand Duchy of Finland. Thus, despite the risks, the smuggling was so useful that it has been estimated some quantity of gold had been brought and sold in Norway, especially during the first years of River Ivalojoki gold rush.

- >

- Exhibitions

- >

- Online and travelling exhibitions

- >

- Law and Order